Saturday, 4 December 2010

Friday, 3 December 2010

Tuesday, 30 November 2010

Thursday, 25 November 2010

Saturday, 20 November 2010

Wednesday, 17 November 2010

Olson at Kent

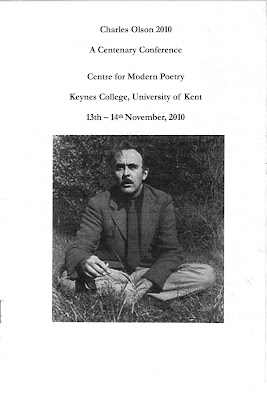

Last weekend the University of Kent held a conference commemorating Charles Olson’s centenary. I feel I should get something down right now about this event though it’s difficult so soon after to begin to unravel the threads that ran through it all. Considering that Olson’s poetry writing career spanned a mere twenty-five years it’s worth considering the effects of his work as a kind of delayed explosion. Most educational institutions apart from one as open as Black Mountain simply haven’t been able to package Olson to suit their needs or, more precisely, the needs pressed upon them by funding bodies. This conference was, in its way, a kind of miracle: it offered a model of what learning ought to be. It brought to life concerns linking Olson’s ideas and practices to our own positions. There have been a few conferences prior to this one celebrating the centenary. If they were as good as the University of Kent’s then 2010 is indeed an annus mirabilus.

Last weekend the University of Kent held a conference commemorating Charles Olson’s centenary. I feel I should get something down right now about this event though it’s difficult so soon after to begin to unravel the threads that ran through it all. Considering that Olson’s poetry writing career spanned a mere twenty-five years it’s worth considering the effects of his work as a kind of delayed explosion. Most educational institutions apart from one as open as Black Mountain simply haven’t been able to package Olson to suit their needs or, more precisely, the needs pressed upon them by funding bodies. This conference was, in its way, a kind of miracle: it offered a model of what learning ought to be. It brought to life concerns linking Olson’s ideas and practices to our own positions. There have been a few conferences prior to this one celebrating the centenary. If they were as good as the University of Kent’s then 2010 is indeed an annus mirabilus.David Herd and Simon Smith and their organising committee coordinated the conference. Contributors included Ian Brinton, Elaine Feinstein, Allen Fisher, Robert Hampson, Ralph Maud, Anthony Mellors, Peter Middleton, Stephen Fredman, Gavin Selerie, Iain Sinclair, Harriet Tarlo, and Robert Vas Dias among others. It’s hard to figure where to begin in recounting such a crowded weekend. A few thoughts will have to do.

A discussion of Olson and women continued through the weekend complicating the notion that ‘projective verse’ is by definition a masculine project. Women are, of course, notoriously absent from Maximus; at most there is ‘woman’, characterised by Susan Howe as ‘cunt, great mother, cow or whore’. Yet many of Olson’s ideas on the process of writing were developed in his correspondence with Frances Boldereff (he suppressed this in his later and more publicised exchanges with Robert Creeley) together with their concerns for Egyptian and Sumerian culture. Boldereff herself was especially interested in the placement of texts on the page (indeed she had trained as a book designer). The ideas behind ‘projective verse’ were also anticipated by Muriel Rukeyser. And of course subsequently Susan Howe has worked in a manner which owes much to Olson (it would have been impossible without him) while being by no means the product of a ‘male poetic’. Olson’s processes of writing involved clearing ‘the gunk out’ and returning to the ‘literal’ (‘the literal is the same as the numeral to me’). ‘The nouns’, said Ed Dorn, ‘seem to become themselves here’. ‘Muthologos’ may have been the mother of a logos (or a mother-of-a-logos!). Field poetics involved field-work and Olson, coming from ‘the last walking period of man’, anticipates eco-poetics, a far from masculine concern.

TJ Clark’s description of modernism as ‘a ruin’ rescues that moment as one we can go back to as historians. I was reminded of Wyndham Lewis’s statement that his own work and that of his associates had become ‘part of a future that has not materialised’. ‘By the end of this century’, Lewis continued, ‘the movement to which, historically, I belong will be as remote as predynastic Egyptian statuary’. Peter Middleton’s fine lecture observed Olson’s science (and his scientism) as they developed in the immediate postwar period that saw scientific discourse become a model for work in other areas. By the year of Projective Verse’s publication the ‘energy field’ had become a paradigm. The concern with ‘measure’ ties up with all of this. Of course Olson is ‘dated’ by it all, yet we can still return to his work as a ‘great fire source’.

Olson’s reception in Britain (both physical and intellectual) was also addressed. He had indeed conducted archival research for Maximus in Dorchester in 1966 (here I couldn’t help but imagine all six foot seven of him crouching in a village pub). That year, I reflected, a twenty year old Englishman called Kris Hemensley moved to Melbourne, Australia, taking with him word of Olson (The New American Poetry had preceded him but Hemensley was both a practitioner and a persuasive advocate). In 1967 Olson read at the Queen Elizabeth Hall on Southbank. His work along with that of others connected with Cid Corman’s journal, Origin, had begun to percolate into the Isles in the 1950s, largely through the work of Gael Turnbull. The notion that ‘I’m going to move on or break it as soon as it happens’ starkly contrasted with the ‘books are crap’ postures of the Movement. It appealed strongly to a number of poets whose work still exists outside the sanctified realm of the TLS and LRB. Gavin Selerie noted that the Scottish poet/playwright Tom McGrath formed a jazz group named after one of Olson’s essays, ‘Proprioception’.

Ralph Maud gave a generous and self-deprecating account of his own contacts with Olson, framing a film featuring the poet reading several pieces including ‘The Librarian’. Iain Sinclair ended the conference with a peroration worthy of the time he spent at Trinity College, Dublin. In this he noted of the film that Olson’s eyebrows appeared like ‘two mice that had swum all night in a sea of ink’. He contrasted the ‘outward’ nature of Olson’s work and influence with the inward (and right-wing) turn of another of Gloucester’s former inhabitants, HP Lovecraft.

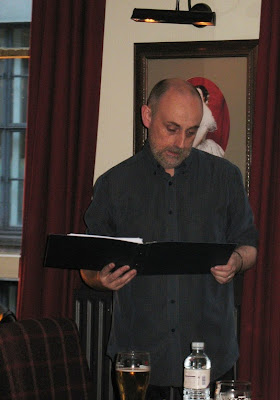

Six of us read poems over the Friday and Saturday evenings, if anything showing what a ‘various art’ Olson’s influence has produced. And Simon Smith and Matthew from Manchester University Press kept the bookstall going throughout. I picked up Ralph Maud’s new edition of Muthologos along with Proposals, a new and self-published book by Allen Fisher featuring his remarkable artwork alongside the poems.

Why has Olson slipped off the agenda? This was one of many questions addressed at the conference. I remember how university libraries both here and in Australia were much more receptive to recent American poetry and poetics up until around 1975 or so when the collections ceased to be adventurous. Ian Brinton noted the way the schools have begun to teach poetry, reducing the area to a few select and easily ‘teachable’ texts (Simon Armitage and his ilk) thus smothering the students’ interests while at the same time boosting the school’s reputation for securing grades. The impingement of ‘market forces’ (soon, under the Conservative government, to become an avalanche) was in the air. Australian right-wing commentator, the late Paddy McGuinness, once figured that the humanities were ‘bullshit’ (unlike economics, which was a ‘science’). Britain’s government seems about to put his less than eloquent theory into practice. So there was a slight valedictory feeling about the conference. If there is such a thing as justice this gathering should be a beginning, not an end.

Thursday, 11 November 2010

Southeastern rant

Back in the Thatcher era somebody had the bright idea of privatising the rail services. The move was made probably with the strange mixture of free market ideology and a remembrance of childhood train sets and their colourful liveries. Though some things are not to be regretted (the Britrail pizza for instance) the shift to private companies has not delivered benefits to anyone much. After the Potters Bar disaster of 2002, Network Rail had to rescue maintenance from private outsourcing. Whoever had been responsible simply didn’t want to spend money with no obvious and immediate return. As for the rail companies themselves, the promised benefits of ‘competition’ were never realised. Since each company operates in a different region it’s hard to see how competition is supposed to work. When an announcement on my train says ‘thank you for travelling with Southeastern’, I wonder what other choice I might have had. Railway fares, already grossly exorbitant, are expected to rise again sharply very soon. My town, Faversham, now has a ‘fast’ service costing some 30 to 50 percent more than the ‘slow train’. It’s convenient for me to get to St Pancras rather than Victoria station but in fact the service is at most only ten minutes faster than the old one. To ensure that there appears to be a difference the ‘slow’ train has been made a little slower through the addition of a couple of stops. The ‘fast’ train has no onboard food and drink service, unlike the ‘slow’ one. But even worse (and I say this as a writer) the fast train has constant announcements, making it virtually impossible to read or to concentrate on anything. How many times to we need to be welcomed aboard? Between Gravesend and Strood, a matter of six or seven minutes, this announcement will often be repeated as much as five or six times. We are told when we are about to arrive somewhere (possibly useful), when we have arrived (possibly not), and what the next stations are. We are informed not to leave our baggage on the train (thanks). Often enough the conductor (sorry, the ‘manager’) repeats the same things. The best announcement though (if ‘best’ is a word that applies here) is the one suggesting that we should ‘make use of the luggage racks to leave room for other passengers’. I imagine nervous besuited business types cramming themselves into the overhead spaces to free the seats below.

Back in the Thatcher era somebody had the bright idea of privatising the rail services. The move was made probably with the strange mixture of free market ideology and a remembrance of childhood train sets and their colourful liveries. Though some things are not to be regretted (the Britrail pizza for instance) the shift to private companies has not delivered benefits to anyone much. After the Potters Bar disaster of 2002, Network Rail had to rescue maintenance from private outsourcing. Whoever had been responsible simply didn’t want to spend money with no obvious and immediate return. As for the rail companies themselves, the promised benefits of ‘competition’ were never realised. Since each company operates in a different region it’s hard to see how competition is supposed to work. When an announcement on my train says ‘thank you for travelling with Southeastern’, I wonder what other choice I might have had. Railway fares, already grossly exorbitant, are expected to rise again sharply very soon. My town, Faversham, now has a ‘fast’ service costing some 30 to 50 percent more than the ‘slow train’. It’s convenient for me to get to St Pancras rather than Victoria station but in fact the service is at most only ten minutes faster than the old one. To ensure that there appears to be a difference the ‘slow’ train has been made a little slower through the addition of a couple of stops. The ‘fast’ train has no onboard food and drink service, unlike the ‘slow’ one. But even worse (and I say this as a writer) the fast train has constant announcements, making it virtually impossible to read or to concentrate on anything. How many times to we need to be welcomed aboard? Between Gravesend and Strood, a matter of six or seven minutes, this announcement will often be repeated as much as five or six times. We are told when we are about to arrive somewhere (possibly useful), when we have arrived (possibly not), and what the next stations are. We are informed not to leave our baggage on the train (thanks). Often enough the conductor (sorry, the ‘manager’) repeats the same things. The best announcement though (if ‘best’ is a word that applies here) is the one suggesting that we should ‘make use of the luggage racks to leave room for other passengers’. I imagine nervous besuited business types cramming themselves into the overhead spaces to free the seats below.Wednesday, 10 November 2010

RADI OS

Last night’s reading at The Lamb, featuring Rachel Lehrman, James Wilkes and Christopher Gutkind, typified the lively and eclectic nature of many of the London readings these days. Rachel Lehrman moved here in 2002 after completing an MFA at the University of Arizona. She launched her first book, Second Waking (in Oystercatcher’s very attractive pamphlet series), then read from works in progress. James Wilkes has done a great deal of collaborative work (often with Holly Pester) but his accompanists this particular evening were a set of radios. These already antiquated objects gave forth a charming mix of voice and static. In the break Harry Gilonis said to me ‘they won’t be able to do this when the conversion to digital is complete. It reminded me of some of the radio collages produced in Germany in the sixties and seventies that I’d listened to back in my media teaching days. Wilkes handles it all with an impressive calm. He also read from Conversations After Dark (Sideline Publications). Chris Gutkind came here from Montreal in the late eighties but didn’t publish a full collection until Inside to Outside (Shearsman) in 2006. He read newer work from Options (Knives Forks and Spoons Press) and Making the World Better (a pamphlet from Kater Murr’s Piraeus series). This poem was a scroll-like reading of another event on another 9/11.

Last night’s reading at The Lamb, featuring Rachel Lehrman, James Wilkes and Christopher Gutkind, typified the lively and eclectic nature of many of the London readings these days. Rachel Lehrman moved here in 2002 after completing an MFA at the University of Arizona. She launched her first book, Second Waking (in Oystercatcher’s very attractive pamphlet series), then read from works in progress. James Wilkes has done a great deal of collaborative work (often with Holly Pester) but his accompanists this particular evening were a set of radios. These already antiquated objects gave forth a charming mix of voice and static. In the break Harry Gilonis said to me ‘they won’t be able to do this when the conversion to digital is complete. It reminded me of some of the radio collages produced in Germany in the sixties and seventies that I’d listened to back in my media teaching days. Wilkes handles it all with an impressive calm. He also read from Conversations After Dark (Sideline Publications). Chris Gutkind came here from Montreal in the late eighties but didn’t publish a full collection until Inside to Outside (Shearsman) in 2006. He read newer work from Options (Knives Forks and Spoons Press) and Making the World Better (a pamphlet from Kater Murr’s Piraeus series). This poem was a scroll-like reading of another event on another 9/11.Sunday, 7 November 2010

Friday, 5 November 2010

at the Swedenborg

Tuesday evening’s Shearsman reading featured David Sergeant and Ian Davidson, who launched another great collection Partly in Riga. Also on the table was the new Collected Poems of Karin Lessing. It’s a timely gathering. Lessing is a Europen-born American who has been living in Provence since the early sixties. Her work is spare, in the Objectivist tradition. August Kleinzhler put me on to her first volume, The Fountain, when I was visiting San Francisco in 1987. I missed a deal of her work however, so this is a welcome addition to the library.

Tuesday evening’s Shearsman reading featured David Sergeant and Ian Davidson, who launched another great collection Partly in Riga. Also on the table was the new Collected Poems of Karin Lessing. It’s a timely gathering. Lessing is a Europen-born American who has been living in Provence since the early sixties. Her work is spare, in the Objectivist tradition. August Kleinzhler put me on to her first volume, The Fountain, when I was visiting San Francisco in 1987. I missed a deal of her work however, so this is a welcome addition to the library.Friday, 29 October 2010

Friday, 22 October 2010

Friday, 15 October 2010

Thursday, 14 October 2010

Bloomsbury to Shoreditch

Tuesday night’s Blue Bus reading was a mixed bag though in all fairness I was only there for the first session. I have to say that I found fellow Australian Hazel Smith somewhat disappointing. The poems seemed to exist in a netherland between performance and the printed page. While this is never a problem with the great performers (in Australia I think of people like Pi O, Nigel Roberts and Joanne Burns) these pieces seemed at best like mildly confessional works at worst not engaging with language as other than a transparent bearer of information. Robert Sheppard who, by the way, is a terrific performer, read new work including a section from his Knives Forks and Spoons Press book The Given. This book makes use of old diary entries, restructuring them so that one section (for example) consists only of questions, another of material written only in May. Though this may seem a fairly rigid schema it came across as quite lively. Sheppard read a section that was a kind of inverse Joe Brainard ‘I remember’ poem. In this case what was listed were the things noted in the diaries that he couldn’t remember.

Tuesday night’s Blue Bus reading was a mixed bag though in all fairness I was only there for the first session. I have to say that I found fellow Australian Hazel Smith somewhat disappointing. The poems seemed to exist in a netherland between performance and the printed page. While this is never a problem with the great performers (in Australia I think of people like Pi O, Nigel Roberts and Joanne Burns) these pieces seemed at best like mildly confessional works at worst not engaging with language as other than a transparent bearer of information. Robert Sheppard who, by the way, is a terrific performer, read new work including a section from his Knives Forks and Spoons Press book The Given. This book makes use of old diary entries, restructuring them so that one section (for example) consists only of questions, another of material written only in May. Though this may seem a fairly rigid schema it came across as quite lively. Sheppard read a section that was a kind of inverse Joe Brainard ‘I remember’ poem. In this case what was listed were the things noted in the diaries that he couldn’t remember.

Wednesday night’s Crossing the Line reading was the first I’ve attended at the new venue: the William IV pub near Old Street tube. The readers were Susana Gardner, over from Switzerland, Simon Smith and myself. I’d feared a low turnout, especially since the reading coincided with a talk by Allen Fisher elsewhere, but the upstairs room was full. Simon Smith read from his new Salt volume London Bridge. I’d not heard Susana Gardner read before but she was impressive. All in all a great reading to have been part of.

Wednesday night’s Crossing the Line reading was the first I’ve attended at the new venue: the William IV pub near Old Street tube. The readers were Susana Gardner, over from Switzerland, Simon Smith and myself. I’d feared a low turnout, especially since the reading coincided with a talk by Allen Fisher elsewhere, but the upstairs room was full. Simon Smith read from his new Salt volume London Bridge. I’d not heard Susana Gardner read before but she was impressive. All in all a great reading to have been part of.Sunday, 10 October 2010

the right stuff

For a brief three days the pottery of Tony Ross-Gower was on display at Faversham’s Creek Creative studios. Remarkably this was his first show (he has been throwing pots for some 37 years). It was an impressive and enjoyable show. Ross-Gower notes his indebtedness to the studios of Bernard Leach and Hamada Shoji and this is apparent in the work. But with pottery the obsession with ‘originality’ is of far less importance than the ‘right feel’ of the work (would that some of the other arts took this aboard).

For a brief three days the pottery of Tony Ross-Gower was on display at Faversham’s Creek Creative studios. Remarkably this was his first show (he has been throwing pots for some 37 years). It was an impressive and enjoyable show. Ross-Gower notes his indebtedness to the studios of Bernard Leach and Hamada Shoji and this is apparent in the work. But with pottery the obsession with ‘originality’ is of far less importance than the ‘right feel’ of the work (would that some of the other arts took this aboard).Wednesday, 6 October 2010

old hat speaks

One of John Latta’s posts from last month offered the glimpse of a world where Jack Spicer may have had a more benign input than Charles Olson. It had me thinking once more about the ways we learn to write poems in a world of shifting directives. When I began to write, my models were blundered into, more or less. They were an often conflicting set of sources and I was naive enough not to perceive or at least to worry about this. Once I began to read Ezra Pound everything changed. My poetic was informed by reading lists, with ‘dos and don’ts’. To some extent Charles Olson’s example confirmed this process. Of course it is very attractive for a young writer to have things so mapped out, and it is undoubtedly educative, but ultimately it may lead to a dead-end. The law-giving poets remain great but their greatness resides in their idiosyncrasies, not in any reproducible formulae. I’d honour Basil Bunting’s self-description as a ‘minor poet not conspicuously dishonest’. It’s the best we can aspire to (though the older BB nonetheless developed a liking for cup-bearing female adolescents).

The head honchos of Langpo behave as though a dictatorial modernism were still available, yet the language of the ‘post-avant’ often has another edge to it. In its rhetoric of constant innovation it resembles nothing more than the ethos of late capitalism, where redundancy has no connection with utility. The new model is good just because it is the new model. All else is consigned to oblivion. Looked at from this angle, Ron Silliman’s poetics resemble the reductive path pursued by Clement Greenberg (What baby? What bathwater? What bathtub?). Significantly the lawmakers of the ‘post-avant’ world tend to be men. These oligarchs present themselves as outsiders while exercising a considerable institutional power which is tenaciously and constantly affirmed. They must live with their own fears of redundancy I guess. At least I hope they do, otherwise they’d be Stalinists.

The head honchos of Langpo behave as though a dictatorial modernism were still available, yet the language of the ‘post-avant’ often has another edge to it. In its rhetoric of constant innovation it resembles nothing more than the ethos of late capitalism, where redundancy has no connection with utility. The new model is good just because it is the new model. All else is consigned to oblivion. Looked at from this angle, Ron Silliman’s poetics resemble the reductive path pursued by Clement Greenberg (What baby? What bathwater? What bathtub?). Significantly the lawmakers of the ‘post-avant’ world tend to be men. These oligarchs present themselves as outsiders while exercising a considerable institutional power which is tenaciously and constantly affirmed. They must live with their own fears of redundancy I guess. At least I hope they do, otherwise they’d be Stalinists.

the season begins

Last night’s reading at the Swedenborg Hall demonstrated two distinct styles of presentation. Adrian Clarke rocked back and forward as many of the poets I’ve seen who have had connections with Bob Cobbing’s Writers Forum tend to do. Peter Riley stood still. You could characterise this as a ‘Cambridge’ position though I don’t think Peter would be altogether happy with that. It did mean that he was easier to photograph. My camera suffers from a slight delay when using the flash and Adrian almost always managed to duck behind Colin Still's recording mikes at the wrong time.

It was the first Shearsman post-summer reading and a fine one. Adrian Clarke read from Eurochants: dense, fast-moving poems with many voices. Peter Riley read from The Derbyshire Poems, a book that brings together three collections from the seventies and early eighties together with two essays written in the same period as glosses more or less. I’ve had Lines on the Liver (Ferry Press) and Tracks and Mineshafts (Grosseteste) since 1985 when I picked them up at Melbourne’s Collected Works bookshop. The other materials would have been harder to come by but now we have the whole sequence available.

Thursday, 30 September 2010

Wednesday, 29 September 2010

Friday, 24 September 2010

whitstable solo

Saxophonist Evan Parker just happens to be a local. I’ve been listening to his recently released disc whitstable solo, recorded in the church of St Peters in that town just up the A299 from Faversham. It’s an extraordinary performance beautifully captured. My uncle, so it happens, was a recording engineer himself and in the early sixties with minimal miking made an atmospheric record of a church choir in outer Melbourne. In these contexts the building itself is ‘played’ as an instrument. I wasn’t fortunate enough to be at Parker's performance, but Harry Gilonis was, and he has contributed a poem ‘written only whilst listening to the music recorded on that night’. ‘a breath of air’ remarkably takes its stanza structure and rhyme scheme from Arnaut Daniel, the Occitan poet.

Saxophonist Evan Parker just happens to be a local. I’ve been listening to his recently released disc whitstable solo, recorded in the church of St Peters in that town just up the A299 from Faversham. It’s an extraordinary performance beautifully captured. My uncle, so it happens, was a recording engineer himself and in the early sixties with minimal miking made an atmospheric record of a church choir in outer Melbourne. In these contexts the building itself is ‘played’ as an instrument. I wasn’t fortunate enough to be at Parker's performance, but Harry Gilonis was, and he has contributed a poem ‘written only whilst listening to the music recorded on that night’. ‘a breath of air’ remarkably takes its stanza structure and rhyme scheme from Arnaut Daniel, the Occitan poet.Thursday, 23 September 2010

Wednesday, 15 September 2010

boys from the black stuff

In this world of right wing think-tanks things slowly fall apart. Elsewhere the black economy of poetry keeps a few people in drinks if not alive. Last night’s Blue Bus reading certainly did this with a good turnout for a great event. Ken Edwards gave a London launch for his new Oystercatcher book Red & Green then read from recent work. Red & Green, presented in its entirety, comes from a longer work entitled Bardo: forty-nine prose pieces over seven days, a rewrite of the Bardo Thodol with the port of Hastings as backdrop. Though Ken is working mostly in prose these days this book had the texture of poetry. Harry Gilonis has often commented on the sparsity of his own productions but one shouldn’t take his self-deprecation that seriously. Not on the strength of the two books launched last night: Reading Holderlin on Orkney, a reprint of a 1990s work from Brae Editions and a new Veer book, eye-blink, consisting of translations (or ‘faithless rewritings’)of eight classical Chinese poets. I highly recommend all of these books.

In this world of right wing think-tanks things slowly fall apart. Elsewhere the black economy of poetry keeps a few people in drinks if not alive. Last night’s Blue Bus reading certainly did this with a good turnout for a great event. Ken Edwards gave a London launch for his new Oystercatcher book Red & Green then read from recent work. Red & Green, presented in its entirety, comes from a longer work entitled Bardo: forty-nine prose pieces over seven days, a rewrite of the Bardo Thodol with the port of Hastings as backdrop. Though Ken is working mostly in prose these days this book had the texture of poetry. Harry Gilonis has often commented on the sparsity of his own productions but one shouldn’t take his self-deprecation that seriously. Not on the strength of the two books launched last night: Reading Holderlin on Orkney, a reprint of a 1990s work from Brae Editions and a new Veer book, eye-blink, consisting of translations (or ‘faithless rewritings’)of eight classical Chinese poets. I highly recommend all of these books. Sunday, 5 September 2010

Thursday, 2 September 2010

Monday, 30 August 2010

Wednesday, 25 August 2010

further along

John Latta has now published Kent Johnson’s reply to Tony Towle’s letter on the attribution of Frank O’Hara’s poem ‘A True Account of Talking to the Sun at Fire Island’. I’m not sure that Johnson’s refutation of Towle’s argument is convincing, though he suggests himself that all he’s really arguing for is a position of reasonable doubt. What do I think about this? Other than coming up with a kind of Ockham’s Razor type argument (i.e. let’s go with the proposition that needs the least structuring) I can’t say that I have any strong feelings on the matter. Do I care whether or not Christopher Marlowe wrote ‘Shakespeare’? Not really, though in the current age of celebrity authorship seems to matter so much more. Johnson’s book might be his own route to celebrity in the ‘bad boy’ mode.

I have often played with the notion of authorship myself and as I’ve said elsewhere on this site one of my earliest influences was a poet who wasn’t a poet (or a person) at all: Ern Malley. My interaction with other poets has, to an extent (I hope), kept the faith. Back in the early 1980s John Scott asked me for lines and fragments from poems I hadn’t completed. From these, and with considerable additions of his own, he composed the poem ‘Breath’ which both of us then printed in our respective books. Just a few years ago I composed a poem merely by breaking into short lines a couple of sentences from a letter Pam Brown sent me. The lines had suggested the rhythm of a Noel Coward lyric so the piece became ‘Pam becomes Noel Coward’. It was included in a book co-authored by Pam, Ken Bolton and myself entitled Let’s Get Lost. Within this book individual poems were not attributed. Pam subsequently published the poem as ‘My Noel Coward’ in her own book Authentic Local. At these levels authorship is a less than obvious proposition. Best of all though was another case from the early 1980s. I had written a group of parodies of my contemporaries. In one of these (‘Analgesia’) the subject was John Forbes. John so much liked the lines with ‘a cowboy riding out of/the bookshelf on a bottle/of brightly coloured pills’ that he used them in his own poem ‘Monkey’s Pride’ as ‘a cowboy appears from a bookcase/riding on a bottle of pills’. It was a double-edged honour. The lines seem so much his that it now appears as though I simply lifted them (as I had done with lines from other poets) and placed them in my own poem.

I have often played with the notion of authorship myself and as I’ve said elsewhere on this site one of my earliest influences was a poet who wasn’t a poet (or a person) at all: Ern Malley. My interaction with other poets has, to an extent (I hope), kept the faith. Back in the early 1980s John Scott asked me for lines and fragments from poems I hadn’t completed. From these, and with considerable additions of his own, he composed the poem ‘Breath’ which both of us then printed in our respective books. Just a few years ago I composed a poem merely by breaking into short lines a couple of sentences from a letter Pam Brown sent me. The lines had suggested the rhythm of a Noel Coward lyric so the piece became ‘Pam becomes Noel Coward’. It was included in a book co-authored by Pam, Ken Bolton and myself entitled Let’s Get Lost. Within this book individual poems were not attributed. Pam subsequently published the poem as ‘My Noel Coward’ in her own book Authentic Local. At these levels authorship is a less than obvious proposition. Best of all though was another case from the early 1980s. I had written a group of parodies of my contemporaries. In one of these (‘Analgesia’) the subject was John Forbes. John so much liked the lines with ‘a cowboy riding out of/the bookshelf on a bottle/of brightly coloured pills’ that he used them in his own poem ‘Monkey’s Pride’ as ‘a cowboy appears from a bookcase/riding on a bottle of pills’. It was a double-edged honour. The lines seem so much his that it now appears as though I simply lifted them (as I had done with lines from other poets) and placed them in my own poem.

Sunday, 22 August 2010

Thursday, 19 August 2010

a true account

For a first class refutation of Kent Johnson’s thesis: that Kenneth Koch was the real author of Frank O’Hara’s poem ‘A True Account of Talking to the Sun at Fire Island’, I’d urge those interested to read Tony Towle’s letter, reproduced on John Latta’s blog. What interests me about this case is the readiness among many to believe in the possibility of forgery. Certainly in the age of the web we are only too aware of occasions for ‘appropriation’, but I think the desire to believe Johnson’s ‘true account’ of the ‘True Account’ has a lot more to do with those propensities the editors of tabloids have made steady use of for decades.

Wednesday, 18 August 2010

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)