Tate Modern’s exhibition ‘Constructing a New World: Van Doesburg & the International Avant-Garde’ is the fourth in an overlapping series of shows (‘Albers & Moholy-Nagy: From the Bauhaus to the New World’, ‘Duchamp, Man Ray, Picabia: The Moment Art Changed Forever’, and ‘Rodchenko & Popova: Defining Constructivism’). I missed the first of these shows but have no doubt that, like each of the others, it would have been a curatorial triumph. The current exhibition traces Van Doesburg’s connections from De Stijl through Dada to the Bauhaus and includes a number of artists whose works have appeared in the earlier shows. It’s a rare occasion (and a welcome one) to see so much of Van Doesburg’s own work but its context too is well managed. It is timely to view these works as something other than precursors to Clement Greenberg’s future.

Tate Modern’s exhibition ‘Constructing a New World: Van Doesburg & the International Avant-Garde’ is the fourth in an overlapping series of shows (‘Albers & Moholy-Nagy: From the Bauhaus to the New World’, ‘Duchamp, Man Ray, Picabia: The Moment Art Changed Forever’, and ‘Rodchenko & Popova: Defining Constructivism’). I missed the first of these shows but have no doubt that, like each of the others, it would have been a curatorial triumph. The current exhibition traces Van Doesburg’s connections from De Stijl through Dada to the Bauhaus and includes a number of artists whose works have appeared in the earlier shows. It’s a rare occasion (and a welcome one) to see so much of Van Doesburg’s own work but its context too is well managed. It is timely to view these works as something other than precursors to Clement Greenberg’s future.The exhibition contains paintings, typography, architecture, sculpture, interior design and furniture. Everything is locked, like so much early modernist work, in a moment when idealism hadn’t solidified into lowest common denominator standardisation or, worse, totalitarianism. There’s a sense that the individual artist is no longer a romantic exemplar, no longer a person of unique importance. Skill is essential (the attitude is not to be confused with hazy notions that we are all poets and artists) though skill is something many people might share. There are many admirable works on display yet in several instances the artists themselves are interchangeable. This is in part the product of a vision of the arts combining and contributing to a greater whole, a mode of living.

A part product of this idealism is the mobility of the practitioners. Scanning through the biographies in the catalogue you notice that between half and two-thirds of these artists moved at least once between countries. Many, born in the pre-war provinces of the Austro-Hungarian Empire would have travelled, as artists do, to the centres. Many more were uprooted by global politics and moved in some cases permanently to France or further to the United States. Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack (represented here by an abstract cinema piece) left Germany only to be rounded up in Britain as an alien once war was declared. He was transported to Australia in 1940 as one of the ‘Dunera boys’. Two years later James Darling the enlightened headmaster of Geelong Grammar School secured his release and appointed him art master. He lived in Australia for the remainder of his life.

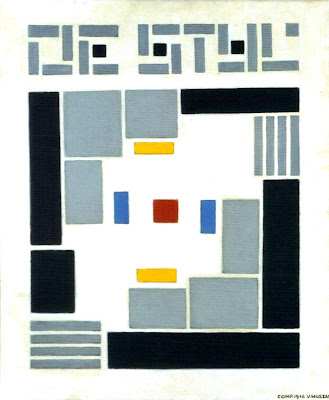

[The works shown above are by Vilmos Huszar, Theo van Doesburg, Gerrit Rietveld, Otto Carslund and Henryk Berlewi]